Ergonomic Product Design: Designing products that humans interact with

Service summary

Ergonomic design can improve the usability, efficiency, and opinion of a product that is physically interacted with. Vivid Nine uses a range of anthropometric data and our experience designing complex ergonomic products to ensure your product works well for its intended user group. This page discusses what ergonomics and anthropometric data are, and why they are an important part of the product design process.

Summary of terms

On this page, we will talk about a few terms related to ergonomics. If you’re not familiar with the terminology or you’re new to product development, here are a selection of the main ones and what they mean.

Expand to read more

Ergonomic design

When a person physically interacts with a product, the way that person interacts with it needs to be considered. The process of designing a product for human interaction is called ergonomics.

Anthropometric data

If you line up a large enough group of people, there will naturally be variation in the range of sizes and proportions. Measurements recording the range of sizes from largest to smallest are called anthropometric data. Good anthropometric data will cover a large user group. The larger the group studied, the more accurate the data will be.

Human factors

Human factors and ergonomics are often used interchangeably, and for most purposes, they are very similar. Human factors cover a wider aspect of human interaction with a product. Where ergonomics mostly focuses on physical interaction, human factors cover physical and psychological aspects. Human factors also cover wider systems involving humans, for instance, how groups of people interact with or think about products, places, or systems.

Percentiles

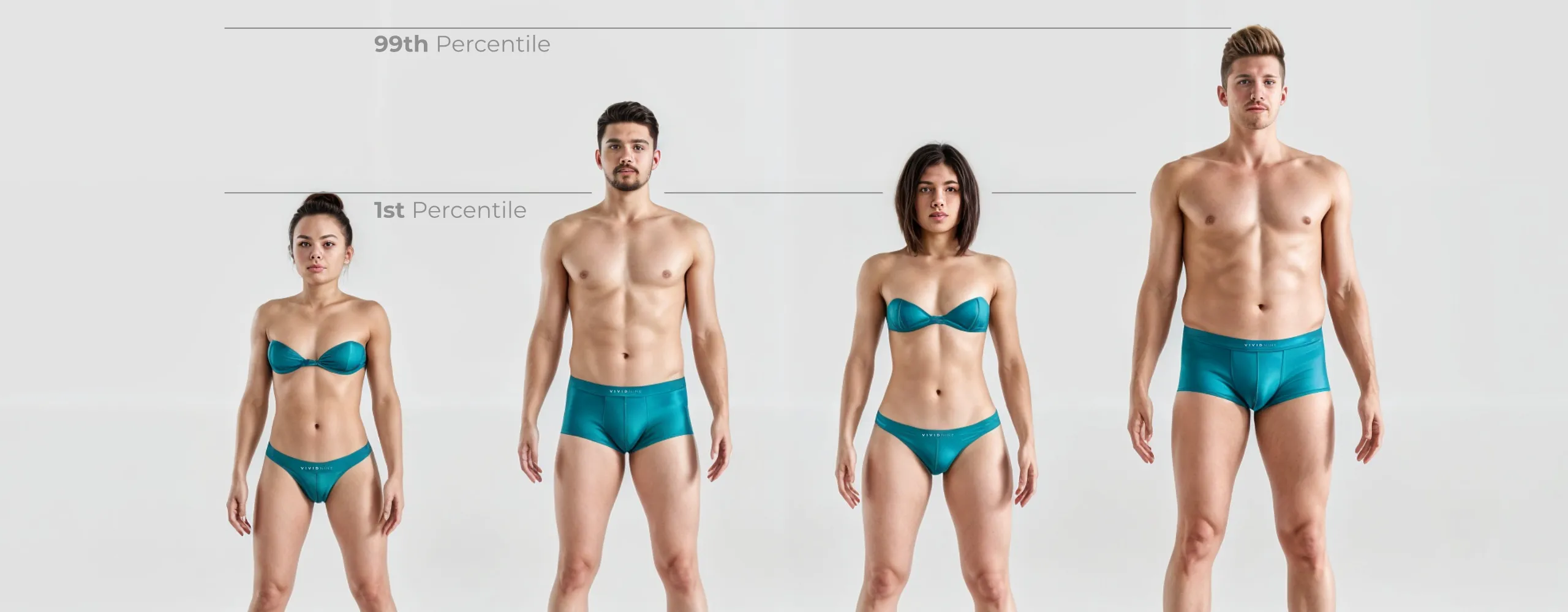

Percentiles describe the differing size ranges in anthropometric data. A 1st percentile describes the lower or smaller end of the scale. The 50th percentile covers the average or most common sizing, and the 99th covers the larger end.

Usability

Usability refers to how a product is used and how well the design allows the product to be interacted with. While the outcome of ergonomic design affects the usability of a product, usability also refers to the wider use of the product, not just from an ergonomics perspective. For instance, the interface or functionality of the product also affects it’s overall usability.

What is ergonomic product design?

There are over eight billion people on the planet, and with such a large number of people naturally comes a variance in physical proportions and size. People who fall within different ranges of this spectrum will experience their environment differently. A taller person may need to bend down for lower doors, whereas a shorter person may find it difficult to reach higher shelves in a kitchen, for example.

Any product that a human interacts with physically requires ergonomic consideration. People differ in many ways: hand sizes, reach distance, head shape, shoulder width, arm diameter, etc. Because of this, it’s important to understand the range of sizes and proportions. What are the smallest, largest, and average sizes in a large group of people? If the product is picked up, worn, carried, has buttons, or is touched, it requires an ergonomic design consideration. The level of ergonomic design and consideration will depend on the level of physical interaction. A product with one button will require less thought and testing than a handheld or headworn product.

The larger the potential user base of a product is, the more likely there will be users with differing sizes and requirements. Getting it wrong can cause a product to be less efficient or even unusable for certain people. Designing a product to suit a larger user may cause problems for a smaller user. Equally, if you design the product to suit the average user perfectly, you may cause issues outside the average.

A product with well-designed ergonomics will feel natural to use for the majority of users. Most people won’t notice a product with good ergonomics, as it won’t stand out to them. Conversely, if you use a product with poor ergonomic design, you will realise very quickly. Uncomfortable, unbalanced, poorly fitting, or hard-to-use products reflect poorly on the perception of the product and the brand behind it.

Using anthropometric data and the product’s intended user demographics, well-functioning solutions can be designed. Physical testing and prototyping are essential, provided you know who you’re testing and where they fit within the anthropometric range.

At Vivid Nine, we use a range of anthropometric data that we’ve collated over the years. We also have many years of experience designing complex ergonomic products. As part of our process, we’ll identify if your product needs ergonomic consideration and highlight which areas are important. Using our data, we can create informed concepts, reducing the amount of time and prototypes required.

What is anthropometric data? Knowing who you're designing for?

Everyone is different, from personality to size and proportions. When it comes to the human body, people vary greatly and in a range of different ways. Proportions are important to understand when designing products for people. Taller people aren’t just a scaled-up version of a shorter person. If a person is 20% taller than another person, not everything will necessarily be 20% larger. For instance, they may be 20% taller but only have 10% longer arms or 5% larger hands. They may even be smaller in other areas. A taller person can have shorter legs than someone shorter overall. In this case, the extra height will be made up from other parts of the body like the torso.

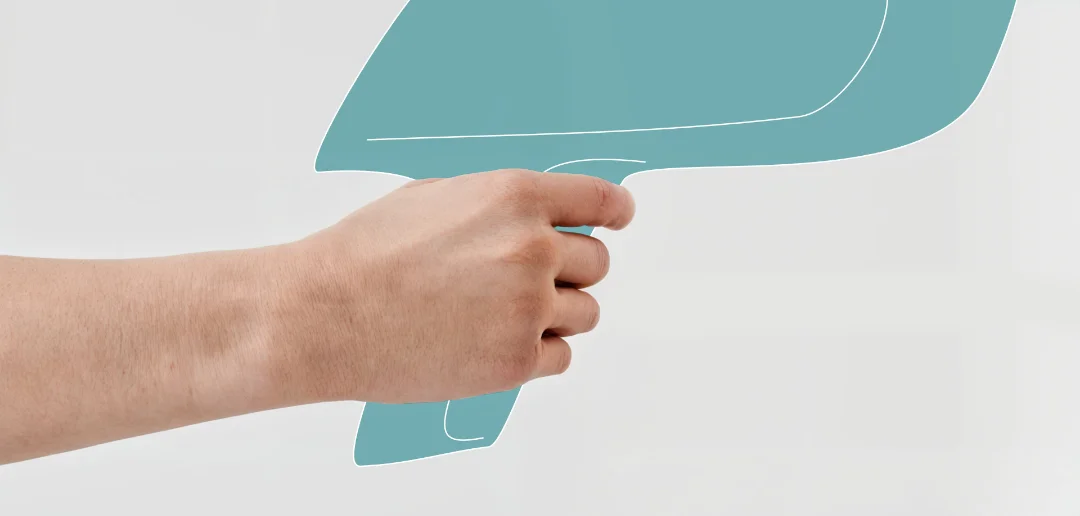

Because of this, it’s important to treat each area of the body somewhat independently. If we’re designing something to go in the hand, we need to know the range of the largest to the smallest hands. Rather than guessing the difference, various studies have been conducted to record the variation across a range of individuals. This is called anthropometric data. The data will normally list a range of sizes from larger to smaller and what is considered average.

This range is measured in percentiles. A 1st percentile will be at the lower end of the range, and the 99th percentile will be at the upper end. A 50th percentile will be the most common size. The larger a product’s user group, the higher the chance that there will be someone closer to a 1st or 99th percentile within it.

Prototyping Ergonomic Designs: The risks to be aware of

Prototyping is an essential part of the product development process, which becomes even more important when it is for a product that a human touches. However, prototyping ergonomic products without anthropometric data is risky.

The problem is that you have no way of knowing where within the potential user range the person testing the prototype is. Imagine you pick up an ergonomic prototype of a handle, and it feels perfect for you. That’s a great start, but you don’t know if your hand is a lower, average, or higher percentile size. If you don’t know where you fit within the user range, you don’t know if you need to allow more room for a larger hand or reduce the diameter for a smaller hand.

Imagine the user testing the product finds it very comfortable. You test the prototype with a few more people who also confirm it’s comfortable for them too. With this confidence, you go ahead and manufacture the product. But when it’s released onto the market, you get complaints or dissatisfied customers. After further research, you realise that the people you tested with are all of a similar size, and the product suits them perfectly. However, they were all towards the larger end of the user range. When smaller users interacted with the product, they found it too bulky and uncomfortable.

Thankfully, if you have the correct data, the chance of this happening is greatly reduced. You can confidently know where the people testing the product fall within the intended user size range. You can then understand the limitations of the test group and compensate with design adjustments. Having a test group that includes a 1st, 50th, and 99th percentile user would be ideal, however, unless you are lucky, this is generally impractical.

Combining anthropometric data with physical prototyping is always the best solution. Understanding where the tester fits on the range and testing with as many people as possible will provide the best results. Iterating with ergonomic prototypes quickly and efficiently will help to test multiple designs and provide the greatest chance of a positive user experience. Prototyping with data speeds up development and reduces risk and development costs.

When we prototype ergonomic products and Vivid Nine, we look to learn as much as possible in an efficient way. Early prototypes may be very crude but are lower cost and fast to make. Prototyping is all about answering the question in the fastest and cheapest way and then iterating if necessary. As the design progresses, prototypes will become more refined as we get closer to the final shape and design.

It is estimated that for every $3 spent on workers compensation, $1 is related to ergonomic issues.

Does my product need an ergonomic design?

Many products don’t require ergonomic design or only require minimal consideration. Other products, probably more than most people realise, do require ergonomic design. The main question to ask is, does a person physically interact with my product, and if so, how? Is it held, touched, worn, sat on, etc? The level of consideration will vary depending on the product. If you’re unsure, get in touch to discuss what level of ergonomic consideration your product may require.

Are there products that aren't physically touched that require ergonomics?

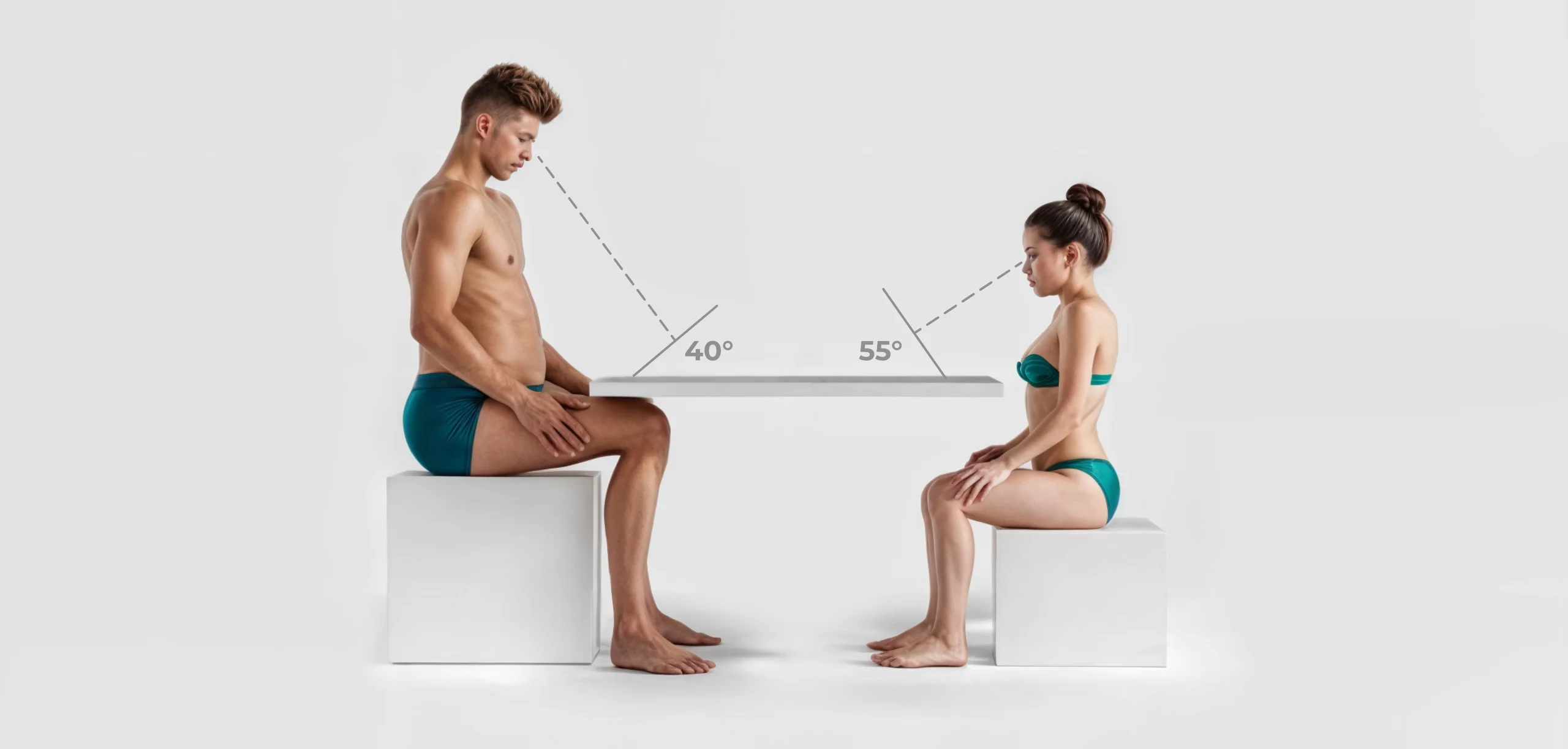

Yes, some products require ergonomic consideration even though they aren’t touched. Screens and signs are good examples. Screens or information displays are typical examples. For instance, a cash machine or an airport departures screen. These are normally at a fixed angle, the chosen angle has been considered based on the eye height of the people viewing it and their distance from the screen. If the angle is wrong, some people may struggle to clearly see the information.

At least 80% of adults will experience one episode of back pain during a lifetime

Examples of ergonomic design in everyday products

There are probably more products than you think that have had ergonomic design consideration. Here is a brief selection of some common ones:

Rucksack

A full rucksack can create a lot of strain on the back if not fitted properly. Because of the large variance in size between people, rucksacks have a wide range of adjustability to allow customisation.

Headphones

Headphones need to fit on the head without falling off during normal use. The sprung central section adjusts to the width without adjustment, and the height of the bar is adjustable to suit the ear position.

Kettle

The handle of a kettle is carefully considered to provide a good grip size for a range of hand sizes. The position and offset from the body also help with balance due to the changing weight when the kettle is empty or full.

Computer Mouse

A well designed ergonomic mouse reduced strain on the hand and wrist. Due to the potential for prolonged usage, even small problems with the design will compound over time.

Tools

The majority of tools require ergonomic design. Handheld tools differ from other handheld products in that they are generally subjected to force or vibration. Because of this, they often require a firmer grip than is necessary for a normal product.

Other Examples

Other examples of products that require ergonomics include:

Binoculars, vacuum cleaner, spray bottle, torch, phone, VR headset, head torch, glasses, ski goggles, earphones, medical equipment, door handle, helmet, tv remote, walking stick, toilet, shower, hair dryer, cold box, chair, bed, laptop screen angle, handrail, tools, wheelchair, gym equipment, toys/baby products, toothbrush, iron, cutlery, frying pan, game controller, camera.

Key Takeaways

- Be careful testing prototypes, make sure you know the approximate percentile range of the people testing the prototype. Make sure you don’t miss other percentile ranges that may not be represented in your test group.

- Poorly considered ergonomics can make a product hard to use or completely unusable for certain percentile groups.

- Creating a product that works for a large percentile range can often be about compromises. Knowing when and where to compromise is the key to a good design.

- Always use anthropometric data, designing an ergonomic product without it, is designing blind.

- Iterate quickly with CAD and physical prototypes. Prototypes don’t need to look good, they are purely to test a theory. Refine and iterate until you’re at a stage where you’re happy it will function well with the range of intended users.